The Google Conundrum

Privacy and Digital Sovereignty⌗

“We must plan for freedom, and not only for security, if for no other reason than only freedom can make security secure.” -Karl Popper

You may have come to this article from a Google search result. You might already be scrolling through your Gmail inbox, curating your Google Photos, or preparing your next road trip with Google Maps. These services have become quintessential parts of many people’s lives, haven’t they? But let’s pause the ordinary for a moment and stroll down the less-taken path. The one I’ve chosen, in which Google services are absent. I might seem like a technology hermit in this digital era, but I have a solid case here. Trust me. I was an early user of Gmail… my first email sent on the service was May 8th, 2004. So, let’s start at the beginning.

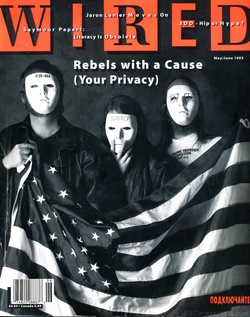

In 1993, while the upcoming Internet revolution was still a few years away from its peak, I stumbled upon Wired magazine’s cover featuring three cypherpunks advocating for privacy and cryptography on the Internet. My family had just recently purchased a Macintosh Performa 400 and a window to this new Internet with it. The privacy argument had a 13-year-old me intrigued, and it was obvious that privacy was not going to be a core concern of the Internet juggernauts of the time (AOL and Yahoo, in this case… Google would only come around later in 1998).

The foundational principle I keep in mind is that privacy is an inherent right, not a privilege or a service to be purchased. We should avoid the bitter pills of authoritarianism sugar-coated with the promises of usability, accessibility, and efficiency.

The Argument Against Google⌗

For me, the primary culprit in this tale of digital intrusion is Google (Meta is not far behind). Though a formidable pioneer in the Internet age, Google has shown an unnerving disregard for privacy. Its business model hinges on the pervasive and indiscriminate collection of personal data. Google uses this information to target advertising, with the individual user turned into a commodity, their every move tracked, their every preference logged.

To put it into perspective, let’s use Gmail as an example. While it provides a seamless email experience, the contents of your emails aren’t entirely private. Google’s automated systems scan and analyze your emails to show you more tailored ads. Google’s exploitation of user data goes beyond Gmail. Its flagship browser, Chrome, is well-documented for its intrusive tracking practices (needless to say, I do not use Chrome.

Likewise, Google Maps logs your location data, creating a chronological map of your daily routines. Even Google Drive and Google Photos, seemingly harmless personal digital vaults, contribute to this vast surveillance capitalism.

As a father and a husband, I have an obligation to ensure my family’s privacy and to educate them on such things. I wouldn’t knowingly let strangers peek into our lives, so why should I let Google? Consequently, I have encouraged my wife and children to leave Google’s services. I have even considered blocking these services at the router level (only to realize that both kids’ schools rely on Chromebooks and Google Classroom).

Why Microsoft and Apple Get a Pass⌗

Now, you might be thinking, “What about other tech giants? Why are they getting a free pass?” Well, it’s not so much a free pass as it is a comparative evaluation. Two ecosystems I continue to selectively use are Microsoft and Apple.

Microsoft’s OneDrive, for instance, has a different revenue model, primarily centered around software sales and subscriptions. They rely less on advertising and data harvesting. Sure, they collect data, but it is considerably less intrusive. Microsoft’s Privacy Statement explicitly states that they don’t use what you type in email, chat, or your documents or photos to target ads to you.

Similarly, Apple’s ‘Privacy is a Fundamental Human Right’ policy has repeatedly shown commitment to user privacy. iCloud storage is encrypted, and Apple doesn’t scan, analyze, or read your content or use machine learning algorithms to sell ads. Their business model is about something other than personal data monetization.

Despite this, I’m not saying these companies are paragons of virtue in the world of data privacy. They all have their issues, but there are degrees of discrepancy, and, in my judgment, Google’s degree of intrusion significantly overshadows that of Microsoft or Apple.

The Road Ahead⌗

Does my path involve certain inconveniences? Absolutely. Transitioning from Google’s suite of services might take you some work… it certainly did for me. But many alternatives are available - ProtonMail for email, DuckDuckGo for search, Signal for messaging, or Nextcloud for cloud storage. Each of these services places a far higher premium on user privacy.

And for transparency, I still retain that old Gmail account and occasionally need to access it when people invite me to a Google Photo share or something of that nature. But it is no longer a regular part of my digital life. Additionally, my town government - in which I play a role - uses Google services like Google Drive and Gmail, so I do have another account there out of necessity.

In a world where our online footprint becomes increasingly more extensive and revealing, privacy is our most precious yet rapidly depleting resource. To quote Christopher Hitchens, “Beware the irrational, however seductive. Shun the ’transcendent’ and all who invite you to subordinate or annihilate yourself.” It’s high time we demand that the products that we use improve their respect for our privacy, place privacy over undue convenience, and uphold our right to remain digitally sovereign. Remember, we’re the customers, not the products. Let’s start acting like it.